People commend my persistence to aid in the relief of five innocent Wisconsin men convicted of murder in 1995. Many others seem bewildered at my desire to do so. But for me, what began as a simple humanitarian effort has turned into a battle between good and evil. I’ve been known to say that if the details of this Monfils case weren’t so tragic, they’d almost be laughable. I’ve witnessed the lives of the innocent dangling on one side of an unbalanced judicial scale as if they are somehow less important, while those on the opposing side expect us to believe in theories that require a creative imagination. My spirit grows weary from the constant rhetoric surrounding the case. And my anger soars as I ponder the reality that this is not about guilt, innocence, or justice, but about career advancement and narcissist pride on behalf of the authorities. With those elements in place, there is no true justice. It’s more about closing a case and ignoring facts; a prevailing factor of all wrongful convictions.

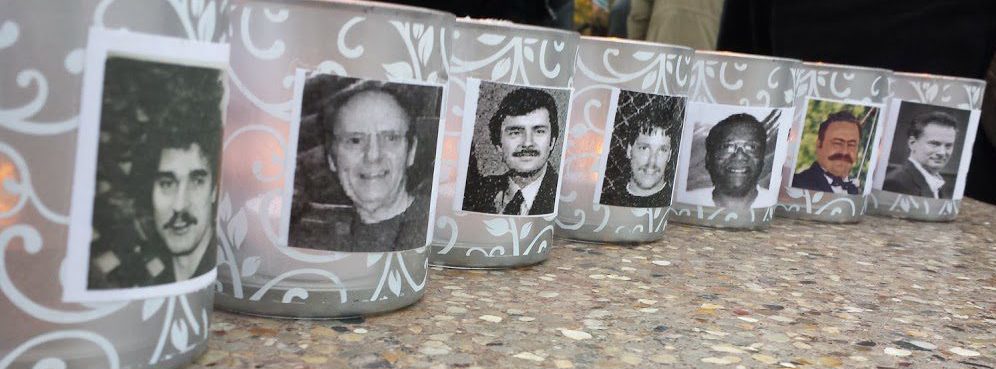

Dale Basten (74 yrs old)*

A thorough examination of this case reveals both the facts and the outcome of six guilty verdicts, are erroneous at best. I’d sure like to believe had I been sitting on the sidelines as a juror in 1995 things might have been different. When jurors were told the series of events leading up to the death were incomplete and riddled with “holes” and “gaps” that could not be rectified, I’d like to believe that I’d have immediately jumped out of my seat and headed for the door yelling at the top of my lungs,”Be sure to call me when those holes and gaps are filled!” Wouldn’t that have been sensational? But would it have made an ounce of difference? Since when is it my place to question the powers that be? And how preposterous of me to challenge those who’d like to think they’re smarter than me or any of the actual jurors? But what is most unfortunate is that not enough of us demand answers for things we find preposterous.

Reynold Moore (70 yrs old)*

There’s much to absorb with the three-day evidentiary hearing now behind us. As we embark on an excruciating long waiting period, hoping the court’s ruling will be swift and favorable, I avoid contemplating the possibility that our efforts could fail despite the damning evidence that was presented. Each passing day represents a harsh reminder of what my friends; Keith Kutska, Reynold Moore, Michael Johnson, Dale Basten and Michael Hirn have endured every single day for twenty+ years. And there’s the nagging question regarding the exoneration of Michael Piaskowski in 2001; the only exoneration in this case so far. How is it that six men were tried together but only one of them has been freed?

Michael Johnson (68 yrs old)*

I cannot help but contemplate other thought-provoking questions. When will this nightmare end? What will be the prevailing factor? And when those prison doors do finally open, will adequate monetary compensation be available for the many years lost?

Keith Kutska (64 yrs old)*

On September 2, 2015, a ninety-page document was filed with a vast amount of new evidence. It supports the belief that this was not murder but a likelihood that the victim, Tom Monfils, took his own life.

In the past six years amid all the twists and turns on an unrelenting road to freedom, I’ve given up trying to make sense of the madness. And I’ve yet to get through a single one of these documents without the usual indignation…

Michael Hirn (51 yrs old)*

*All images courtesy of artist/writer Jared Manninen