The promise of a new year incites good intentions, great new beginnings and a longing to leave undesirable baggage behind. A new year….a new us, right? Gym memberships soar, diets commence and monthly planners designed to organize our crazy lives fly off the shelves. These are great concepts that seldom pan out. Why? Because our hearts are not sufficiently vested. And the actual energy needed to maintain them becomes overwhelming because all that has really changed is the calendar year.

But the good news is that we are a resilient species. We never give up entirely. And we believe that our persistence will produce something fruitful.

With that said, I’d like to introduce you to someone very special to me; someone I feel could be a poster child of tenacity and determination; someone who came into my life and taught me how to withstand terrible odds. I met her while advocating for the same cause; the plight of six innocent men from Green Bay, Wisconsin. Coming from opposite sides in a common fight, mine as an outsider and hers as an insider, our friendship has become strong and steady. It has helped us to maintain hope that her situation will eventually improve.

Joan Van Houten started this New Year off the same as she has for the past twenty+ years; positive and determined despite a significant and ongoing conflict she deals with daily. Joan remains steadfast in her mission to free a loved one from prison; someone she believes…she knows is innocent. And her 2016 resolutions precipitate being more active and successful at this one thing.

Each year Joan pushes herself that much harder to win this impossible fight. Each year she resolves to never abandon her stepfather, Michael Johnson; an innocent man sentenced to life in prison for a murder he did not commit.

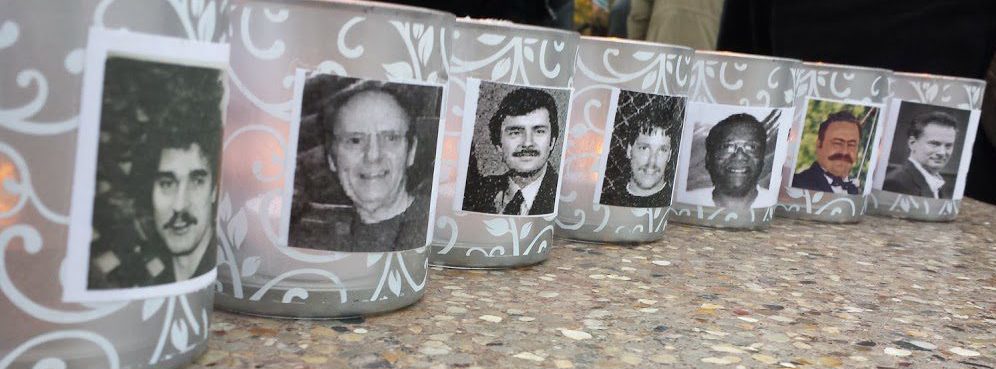

Michael Johnson (as he looked during sentencing) is third from the left

Joan recently wrote these brutally honest and powerful words about her plight. Having collaborated with her in this tragic circumstance, I have witnessed how hard it is for her to relive the painful moments that continue to persist and will do so until Michael’s sentence is vacated. So I felt her voice needed to be featured on my blog…

Note: Michael Johnson is the only one of the five men my husband Mike and I have not visited in prison. We plan to do so in early 2016.

A New Year Brings Renewed Hope

By: Joan Van Houten

Another year has gone and we are left to make choices about how we plan to face the months ahead. Do we look back with disdain and sorrow and pain while looking ahead seeing only more of the same? Or do we choose to hold on to the progress made, all the love, effort and passionate actions of those who have so fully given of themselves to help our families?

Families of those wrongly convicted are not delusional. We would not still be fighting … over twenty years of fighting … because we’re too thick headed to believe someone we love is guilty. There are too many of us who know something went terribly wrong with the investigation into the death of Thomas Monfils. It’s not just one family. It’s not just two families. Six entire family units have been fighting to expose and to right what happened to all of us. And all six families remain committed after all these years. Can anyone still believe that each of us is out of our mind?

Year after year of watching our men in pain. Year after year as their children grew to graduate high school and college, have families of their own and children of their own. Year after year of Wisconsin Court officials turning their backs to the truth. So many of us, from different backgrounds, different histories and different experiences … still here and still fighting. It would be so much easier to just move on. To let go and accept that this is a fate that cannot be changed would be a less heartbreaking road to follow. And yet … we fight. Still.

It’s uncomfortable – talking to reporters from both television and print media. None of us work in that field. None of us are accustomed to standing out in the crowd. We’re everyday people with all the normal problems everyone has. To top that off, we’ve been fighting for the release of men who were convicted of murder. Murder! Though wrongly convicted in a case riddled with horrendous acts that go completely against the ideals set forth for our judicial system … convicted none the less. It can still cut deep when assumptions are made about what drives us to continue on – when our motives are shaved down to nothing more than pure lunacy and grief. To be judged in full public view is a hard thing to go through and the ugliness of some coming with all fangs bared and dripping with hate is something that makes me cringe. And yet … we fight. Still.

It’s been a long road and there is a long road ahead. Looking back, I see the monstrous valleys and paths riddled with boulders – I see the flooded gateways and pitted glaciers covering the earth. All these things that seemed insurmountable … unclimbable … unpassable. And yet, here we are … all those things behind us.

Our numbers have grown and continue to do so. With the book, The Monfils Conspiracy, The Conviction of Six Innocent Men by Denis Gullickson and John Gaie, and the merciful presence of Joan Treppa, a Citizen Advocate who adopted our plight as her own, our supporters reach out, to us and for us, more and more with each passing week. Outrage has finally begun to break through the disbelief and the voices of our men are finally reaching the hearts and ears of the masses.

In the months ahead, Truth will be our banner once again. It will be raised higher than ever imagined and ring louder than corrupt ears will be able to bear. With a new year comes renewed hope. And with Hope, all things are possible.

Joan Van Houten is the step-daughter of Michael Johnson, one of six men wrongly convicted in the death of Thomas Monfils, detailed in the book; The Monfils Conspiracy, The Conviction of Six Innocent Men written by Denis Gullickson and John Gaie. Instrumental in bringing her step-father’s plight of innocence to the attention of renowned attorney, Lawrence Marshall, who took on the fight Pro Bono, she continues the work of bringing awareness of the six wrongful convictions to light.

Links to more information on the book and this case:

The Voice of Innocence is a FaceBook page Joan and I jointly maintain.