This segment examines the ineptitude and legal challenges of the defense attorneys in a joint trial setting.

Ineffective Assistance of counsel…

“The expert report of pre-eminent Wisconsin criminal lawyer, Stephen Glynn, Esq., explains why Kutska’s defense counsel failed to provide the diligent, thorough, and skillful representation that was required in this case and how that failure prejudiced Kutska’s defense and claim of innocence. In particular:

- Kutska’s defense counsel was obligated to (a) consult with and retain an independent forensic pathologist to challenge and disprove, if possible, Dr. Young’s homicide testimony and also to (b) investigate the strong possibility that Monfils had committed suicide. The need to investigate the question of suicide was apparent in light of Monfils’ mental and emotional history, the stresses in his life, his experiences in the Coast Guard, his pre-occupation with death and drowning, and his failed marriage. Instead, defense counsel made the uninformed and catastrophically prejudiced concession of an element of the charge–that Monfils had been beaten and murdered as Dr. Young and the prosecution contended. As Mr. Glynn states, those concessions and failures lacked any strategic justification.

- Had defense counsel investigated the medical examiner’s findings and conclusions and whether Monfils had taken his own life, they would have shown the jury why the prosecutor’s homicide theory was not merely doubtful, but flatly wrong, thereby undermining the credibility of certain key witnesses. Defense counsel’s concessions and failures led the jury to assume instead that the prosecution’s case was based on solidly reliable scientific, medical and other evidence, including the false testimony of the prosecution’s two most critical fact witnesses—Brian Kellner and David Weiner.

- Defense counsel had ample means, including through the use of formal discovery in the companion civil wrongful death litigation, to obtain the evidence with which to develop a powerful suicide defense. Indeed, suicide was then, and still remains, the only theory that is fully consistent with both the evidence that existed and the evidence that did not exist.

- Defense counsel’s concessions and failures limited Kutska’s defense to the sole contention that someone else had beaten Monfils and disposed of his body in the vat. The overriding problem with that defense, however, was that Kutska’s counsel lacked sufficient evidence pointing to anyone who might have done so in the closed environment of the mill. Moreover, Kutska was the person in the mill that day with a proven reason to be upset with Monfils and who had been with and near Monfils in the minutes leading up to Monfils’ disappearance. Kutska was, therefore, the prime focus of the homicide investigation. Defense counsel for the other defendants likewise could not point a convincing finger at anyone (other than one or more of the co-defendants, including Kutska). As counsel for one co-defendant candidly admitted in his closing argument, “[w]e have no theories about this case.” Similarly, in post-conviction proceedings, Kutska’s counsel never (a) attacked Dr. Young’s homicide testimony or the prosecution’s contention that Monfils had been beaten and then deposited into the vat where he died and never (b) investigated or presented the evidence pointing toward Monfils’ suicide.

- Kutska’s counsel was further deficient at trial and in post-conviction by failing to show that (1) Sgt. Randy Winkler’s coercive tactics had corrupted the investigation and the trial with perjured statements and testimony from certain key witnesses; (2) Winkler perjured himself and engaged in other acts of dishonesty; (3) other key prosecution witnesses, including David Weiner, James Gilliam, and James Charleston, also perjured themselves; (4) Weiner had an arrangement or understanding with the prosecution for his testimony that both he and the prosecution denied; and (5) the prosecution’s arguments were illogical, conflicting and made up.

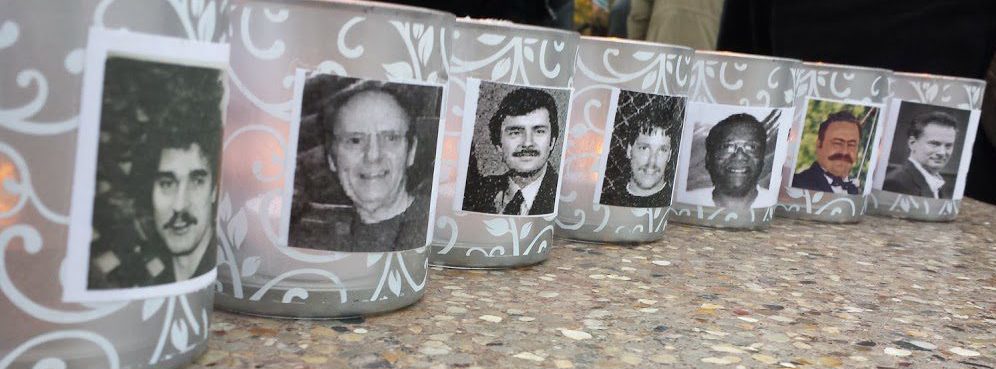

Corroborated Facts: On November 21, 1992, the body of Tom Monfils was found. Approximately two and a half years later, on April 12, 1995, six men were arrested for his alleged murder and on September 26, 1995, a joint trial involving these six men began. Then on October 28, 1995, all six of these men were found guilty of murder.

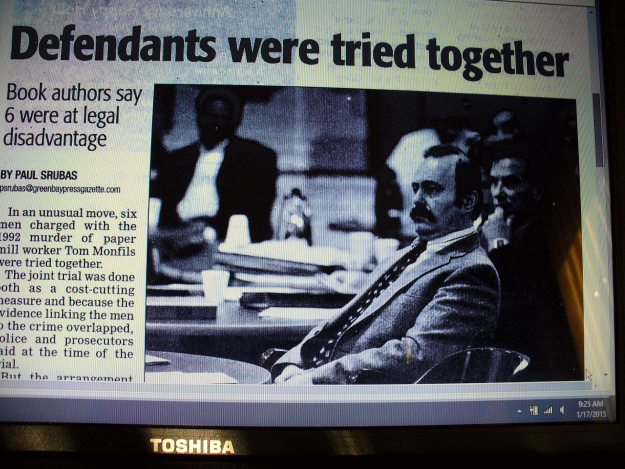

Keith Kutska listens during the Monfils trial in 1995. (Photo courtesy of the Green Bay Press-Gazette)

The trial was conducted as a joint effort with all co-defendants lined up in a row next to their attorneys. The book suggests with separate trials the six men would not have been convicted of murdering Monfils because trying all of the men together automatically destroyed each man’s ability to create an independent defense. The idea that this joint strategy might confuse the jury was an unavoidable consequence. Despite the judge’s directive to the jury that not all testimony pertained to all of the defendants, evidence against one of the men was automatically applied to all of them. This idea was unmistakably evident in a letter from a juror to Mike Piaskowski years after he was exonerated. “It was too much to process and too easy just to make the same judgment for all of the defendants.” Coupled with the complexity of information laid out during the twenty-eight-day trial, three of the six men were named Michael.

The defense attorneys recognized the unfair burden of a joint trial and they filed several pretrial motions demanding separate trials. Tax-dollar savings and consideration of the emotional state of the victim’s family won, compelling the trial judge to deny each of these motions.

There was an order in which each attorney was allowed to question each of the eighty-one witnesses. This system could not be altered during the entire trial. Attorney number one was always given the first opportunity to ask his question. If attorney number five, for instance, was not satisfied with the answer and raised it again when his turn came up, the judge would dismiss it as “asked and answered” and the attorney was told to move on to his next question.

Unfortunately, all of the defense attorneys agreed at the onset of this joint trial to disregard the suicide theory…period! All else aside, this was the most crucial mistake they could have made because, in fact, it was their only defense. That mistake cemented the convictions of all six of these men.