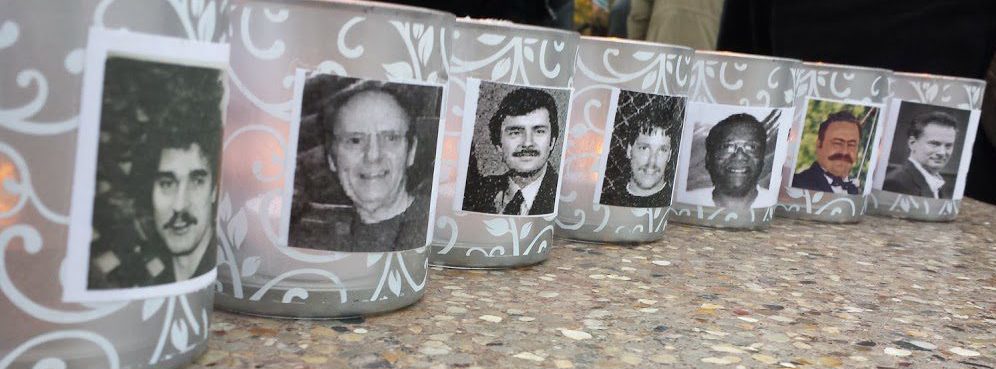

On July 22, 2015 I attended the third and final day of testimony in the evidentiary hearing for Keith Kutska; one of six men convicted in the 1992 death of paper mill worker, Tom Monfils.

Brown County Courthouse during evidentiary hearing

Testimony on this day was especially perplexing. The bulk of it was spent questioning the former lead detective who worked on the Monfils case, Randy Winkler.

Summary:

Evidentiary hearing for Keith Kutska July 22, 2015

Day three:

9:23 a.m. – Eleventh witness:

Attorney Bruce Bachhuber – Practiced business litigation and family law. He was legal counsel for Sue Monfils, wife of Tom Monfils, in a wrongful death lawsuit against all six of the defendants, and later in a separate civil suit against the Green Bay Police Department regarding the release of the audio tape to Keith Kutska prior to Tom Monfils’ disappearance.

Bachhuber had been subpoenaed prior to this hearing by defense counsel to produce Sue Monfils’ medical and marriage counseling records. John Lundquist showed the court and Bachhuber a copy of that subpoena. Bachhuber verified receiving the document. He was asked if he brought any of the stated documents with him, and he said he had not. When asked why, he argued they were protected by attorney/client privilege and that he wasn’twilling to waive it. Discussion ensued about the relevance of the requested documents in regards to the Monfils case and why they should or should not be provided. Bachhuber added other documents listed on the subpoena were no longer in his possession. He stated he had searched for them, but couldn’t locate them. The judge interjected by saying some of the requested documents hadn’t been admitted as exhibits at the wrongful death case trial and weren’t within the scope of what he’d ordered Bachhuber’s firm to produce at the hearing. The documents that Bachhuber did bring were of no relevance to the motion. Bachhuber was dismissed.

9:40 a.m. – Twelfth witness:

Jody Liegeois – Restaurant hostess in Abrams, Wisconsin, 1995–99.

Liegeois said she knew Verna Irish, formerly Verna Kellner, from the restaurant where she was employed because Irish worked at the adjacent gas station and had dined there often. She never met Brian Kellner, but knew he was Irish’s ex-husband. She said Keith Kutska was a friend of Liegeois’ dad, and that Liegeois had met Keith at the family’s home. She followed the trial and was aware of the Irish and Kellner testimony. She had a conversation with Irish about Irish’s testimony. Irish had said she was upset because she and Brian Kellner had been forced to lie about the so-called “bar reenactment” in which Kutska had allegedly showed them how Monfils was beaten at the bubbler.

The DA objected to Liegeois’ answer. It was overruled.

Liegeois said Irish told her that the investigator in the case forced hers and Brian Kellner’s testimony about the reenactment, and that both she and Brian had lied.

The DA objected to the statement about Kellner’s testimony. Steve made offer of proof. The statement was allowed.

Liegeois again stated her knowledge that Kellner’s testimony was forced by Winkler, but she didn’t report it back then because she felt the case was a “done deal.” She contacted Steve Kaplan after hearing news reports regarding the first two days of the evidentiary hearing, and the information stating that Irish and Kellner had lied during the trial. She did so because of what she felt she knew.

The DA pressed that Liegeois knew this twenty years ago, but was only coming forth with it now. She answered yes.

9:50 a.m. – Thirteenth witness:

Gary Thyes – Employed as a barber in Green Bay, 1992–95.

Thyes knew Brian Kellner, and cut his hair for a number of years. He knew of Monfils’ death and of the ongoing investigation. He said he had to kick detectives out of his shop when they brought in statements for him to sign about comments supposedly made by some of his regular customers who worked at the mill. “They made up stories . . . they made up what they wanted me to sign,” Thyes said. Thyes refused to sign any of the statements. He had conversations with Kellner about detectives threatening to take Kellner’s kids away. Kellner also told Thyes he had signed a police statement he later felt bad about signing. They had talked about how Kellner eventually signed the statement when threatened to have his kids taken away. Kellner said he was very upset right after he signed it, and had contacted an attorney about it.

The DA asked if Thyes had ever contacted a defense lawyer. He said he had not and that he didn’t start following the recent developments until he read Kellner’s obituary (in 2014). Furthermore, he didn’t contact Steve Kaplan until he read about the recent hearings. He also said he didn’t know Kellner had testified twice about the reenactment. He said he told Steve Kaplan he could pass a lie detector test in regards to what he knew about Kellner. The DA asked Thyes when his conversation took place with Kellner about signing the statement. He said Kellner had come into the shop shortly after (he signed it) and told him.

10:05 a.m. – Fourteenth witness:

Randy Winkler – Former Green Bay police officer, and detective sergeant. In January of 1994 he became the lead detective for the Monfils case.

Winkler was subpoenaed for this hearing to produce information about his disability settlement with the police department, along with other documents. He was shown a copy of the subpoena, and verified having received it. He was asked if he brought documents specified on the subpoena to the hearing. He said he hadn’t When asked why, he stated attorney/client privilege, as well as doctor/patient privilege.

Winkler learned the body was found two days after Monfils went missing, and that it had a rope and weight attached. He stated he wasn’t part of the initial police team sent to the mill to investigate, but went the following morning. He was looking for trace evidence—blood, hair, tissue, etc. When Steve asked Winkler about looking for evidence of an act of violence at the mill including near the bubbler, he implied Winkler had found none. But Winkler stated this was incorrect. When Steve asked Winkler to clarify his answer and disclose what evidence he was referring to, Winkler stated matter-of-factly that a body had been found. Steve rephrased his prior comment this time excluding the body as the kind of evidence he was alluding to, and reiterated that there was no evidence found anywhere in the mill. Winkler said this was correct. Winkler didn’t recall if luminol was used with black light to search for blood. Winkler believed there was a connection between the 911 call and Monfils’ death.

The autopsy was discussed. Winkler didn’t recall the names of the police officers present. He was asked if he was aware that Dr. Young didn’t believe the death was a suicide. An objection by the prosecution was sustained.

There were repeated objections regarding detail sheets and other documented exhibits Steve produced and showed to Winkler. These were part of the initial investigation, but signed by other officers. The prosecution argued Winkler couldn’t speak for those other officers and the defense should call them (officers) to the stand. Steve contended Winkler was the lead detective of a major case and should be well versed in the contents of these documents. Steve pressed that Dr. Young had influenced Winkler’s opinion that there had been a beating and that this theory guided his investigation, even though there was no eyewitness or physical evidence to support it. None of these exhibits were admitted. They were placed in the record under an “offer of proof.” Steve asked Winkler if the bubbler theory was developed before talking with Brian Kellner. He said yes.

Steve stated the police could never match a blunt object to an injury on Tom’s head. Winkler said this was correct. Steve presented a list of nine suspects generated in December of 1992. Winkler verified the list, and that six of the men on it were later charged. The name David Weiner was on the list and Steve stated Weiner was never charged. Winkler said that was correct. Exhibit was admitted.

Steve stated David Weiner was interviewed on numerous occasions. Winkler said yes. Winkler also said he believed Weiner took a leave of absence from the mill. Asked if Winkler testified that Weiner was an important witness, he said he did not recall. Discussion ensued about Dale Basten and Mike Johnson carrying something heavy. An objection by the DA was overruled.

Steve talked about Tom Monfils’ height and weight and the distance from where Monfils was allegedly beaten and the vat. Steve asked if Winkler believed Weiner saw Basten and Johnson carrying the body to the vat. Winkler said yes. Steve discussed the logistics of carrying Monfils’ body and expressed the added difficulty of having a rope and heavy weight attached.

When asked if Winkler was interested in who tied the knots, Winkler said “yes.” Steve suggested if Monfils had tied the knots, it would lead them to believe he committed suicide. Winkler said “no.” He also stated he assumed a beating had taken place. Steve pressed that Winkler never found anyone who said he saw a beating, and Winkler said this was correct. No eyewitnesses? No. Winkler stated he presumed there were witnesses, and that the mill workers were lying or covering up for fellow mill workers. Winkler stated the knots were sent to the crime lab. When asked if Winkler was told the knots should be sent to the coast guard, he said he didn’t know. Steve produced an exhibit; a detail sheet from December of 1992 that stated that the knots should be checked by the coast guard or the navy. When Steve asked Winkler if the knots were checked by either branch of service, Winkler said he didn’t know and that he never took steps to have them checked. Winkler says he obtained knots that Basten had tied, but didn’t remember if they were the same as on the body and said he didn’t compare them. Winkler didn’t find out if Monfils could have tied the knots, and Winkler stated he didn’t know the type of knot on the rope and weight.

Winkler stated he knew Monfils had a skull fracture, but that it had to come from something other than the vat impeller blade. Steve produced autopsy photos of Monfils’ skull and of the blade edge impressions. Winkler didn’t recall them. He also didn’t recall that a dentist made a cast of the skull. He didn’t recall the width of the wound in the skull or the width of the impeller blade. Winkler said no object was found to match the skull fracture wound. Steve asked if anyone educated Dr. Young on the shape of the blades, and Winkler said he didn’t recall. Steve pressed if any expert had determined what matched the blade, and Winkler said he didn’t recall. Steve expressed his lack of understanding of Winkler’s inability to remember many of the details of the case, despite recent conversations with reporters and filmmakers about the case.

Detail sheets were discussed. Steve asked Winkler if detail sheets needed to be accurate. Winkler said yes. Winkler stated he determined what went into them and that no one else confirmed their contents. Winkler stated they were critical pieces of information used by the police and prosecutors in criminal cases. Winkler typed up witness interviews on his own typewriter. When asked if Winkler recalled visiting Steve Stein at Stein’s home, he said no. Winkler was asked if he conducted surveillance. He replied yes. Were reports written up? Winkler couldn’t say. When asked if he had access to tape recorders, he said yes. Were they (tape recorders) ever used in interviews? Winkler said no, by choice. Steve asked if Winkler conducted about two hundred interviews during the Monfils investigation, and Winkler said it was closer to five hundred. Winkler was asked if he did reports for each interview, and Winkler said no. He stated it wasn’t always necessary. Steve asked Winkler to describe when they weren’t necessary, and Winkler said it was when the content didn’t pertain to the case or if the person didn’t have any information. Steve asked if any interrogations got heated, and Winkler said no. Steve asked whether anyone who stated he (Winkler) did get angry was lying. Winkler said yes. Steve asked if there was a reward for any arrests and convictions, and Winkler said yes. When asked if it was $75,000, Winkler stated he didn’t know. Steve asked if Winkler would tell people there was a reward and he said yes, but added no one said they saw anything.

The Reid Method of Interrogation was discussed. This technique is an accusatory process in which the investigator tells the suspect there is no doubt as to his or her guilt. It is done as a monologue presented by the investigator rather than a question-and-answer format. Winkler stated he was trained in this method. Steve asked how many hours were usually spent to question a witness. Winkler said two to four. Steve asked if it allowed you to lie to the subject, and Winkler said yes. Could you coerce a witness into giving false statements? Winkler said no, but added if witnesses didn’t tell him what he wanted, he would do more of an interrogation. Steve asked if the method allowed you to threaten subjects by saying they would lose their jobs or have their kids taken away if they didn’t tell you something? Winkler said no. Steve asked if Winkler had interrogated Dale Basten for twelve hours, and Winkler said yes.

Winkler said he was authorized by Oconto County to conduct the investigation. When asked if Verna Irish and Brian Kellner lived there, he said he didn’t recall but it was possible. Winkler said he didn’t recall if they (Verna and Brian) had children, but he was aware they were going through a divorce. When asked if he was aware that child custody was an issue, he said he didn’t. Winkler said he met with Brian Kellner to get information on many suspects and when asked if he documented every interview with Kellner, he said yes. When asked if Winkler was aware that someone claiming to be from child welfare visited the Kellner children, he said he had no knowledge of that. When asked if Winkler remembered Kellner asking him to leave his kids out of it, Winkler said he did not.

Steve presented a nine-page detail sheet regarding a 2.75-hour interview from 1994 between Winkler and Brian Kellner. Winkler asked to read the entire document. Afterward, Steve asked if Winkler noticed in the detail sheet that the Fox Den reenactment incident was not referenced. Winkler said yes. Steve presented an exhibit of the statement Kellner signed, and Winkler verified he had prepared it. Steve noted minor changes made with Kellner’s initials; three on one page, one on another, but no substantive changes were made on the document. When asked if Kellner resisted signing the final statement, Winkler said he did not.

Steve asked Winkler if people at the mill told him about Monfils’ obsessions with death and drowning, and Winkler denied ever hearing this. Steve asked if Winkler ever heard Susan Monfils say it was possible that her husband committed suicide, and he said he did not. When asked if he ever obtained Monfils’ medical records, he said he did not know. Winkler said Monfils’ death was ruled a homicide, and that was how it was investigated. Winkler also stated even if Monfils had tied knots, this wouldn’t have determined it was a suicide.

Steve asked Winkler if the DA ever made comments to him about a deal for Weiner after Weiner’s arrest, and Winkler said no. Steve asked if Winkler recalled Weiner stating he wouldn’t cooperate in the Monfils case without a deal, and Winkler said he did not. When Steve showed Winkler a news article containing that statement, Winkler said he still didn’t recall. Winkler said he didn’t recall visiting Weiner at Oshkosh Correctional to obtain writing samples. Steve then produced a letter from Weiner’s lawyer referencing the visit and Winkler’s own detail sheet documenting it. When Steve asked Winkler if he hadn’t told Weiner during the visit that Weiner’s cooperation could improve his position if he cooperated, Winkler said he hadn’t. Discussion ensued about a series of letters from an attorney representing Weiner regarding a deal, including a possible reduced sentence for his testimony. Winkler denied any knowledge of them or that Weiner’s lawyers contacted the DA’s office before the Monfils trial. In fact, Winkler denied having any knowledge of Weiner’s case even though he was still working at the police department.

Steve asked about a psychological disability claim Winkler had filed with the department. The DA objected. Steve argued it went to credibility of a lead detective in a homicide case. It was decided five specific documents in question would be entered under seal, and that both sides would have a chance to argue for or against their relevance at a later time.

The DA asked Winkler about his work history. Winkler stated he was employed by the department in 1975. He rose to the rank of detective sergeant and worked on the Monfils case for three years. Winkler stated it was stressful being subjected to the conditions at the mill, and that he was under constant scrutiny by the men there. He said he received a death threat, and he also said people claimed Monfils got what he had coming. There was a great deal of speculation within the community, and suicide was brought up often. The DA asked if Winkler ever promised to give Weiner a deal for his testimony, and he said he had no authority to make deals.

Steve established Winkler had an office at the mill, that the mill made it clear that job retention was based on the workers’ willingness to “cooperate with police,” and that the office was available to perform interviews. Winkler also clarified that he and other officers brought witnesses to the police station to talk.

In conclusion: Judge Bayorgeon commended Steve on his “diligent” and “amazing” job during this entire hearing, before he admonished him for insinuating a “public servant” (the then- DA Zakowski) lied about a Weiner deal. Bayorgeon stated he had examined all the documentation and could not find anything to suggest a deal was made or that the DA lied about it. He indicated those were serious allegations to be making. He added that specific letters presented at this hearing in regards to such a deal could not support the claim of a deal. He also said it was a twenty-eight-day trial with eighty-one witnesses, and the jury was instructed to consider all witness testimony.

Judge Bayorgeon gave each side time to argue the merits of the sealed documents in writing and to submit briefs on the merits of the motion for post-conviction relief.

Update: On Wednesday, January 13, 2016, the motion for a new trial was denied. Immediately following, a similar appeal was filed in the Wisconsin Court of Appeals. On Wednesday, December 28, 2016 that motion was also denied. The next step was a petition to the Wisconsin Supreme Court. That motion was similarly denied.

A related Green Bay Press-Gazette news story