“Sure. I’d love to visit your class!”

Máel Embser-Herbert; a good friend and sociology professor at Hamline University, contacted me about a Wrongful Conviction course they’d be teaching during the upcoming school year. Máel asked if I’d be available to share my story with the students in the fall, and offered to use my book as a learning tool for them.

A Hamline University campus building as viewed from Snelling Avenue in St. Paul, Minnesota.

“I’d like you to focus on the social aspects of this case such as why you became involved, who the men and their families are, things like that,” Máel explained.

I’ve spoken to high school students in the past and feel my book is likewise appropriate for use on the college/university level. Simply put, it’s written from my non-legal perspective and absent of the hardcore legalese, making it a suitable introduction to this less than desirable aspect of our criminal justice system. A must for those entering into the legal field.

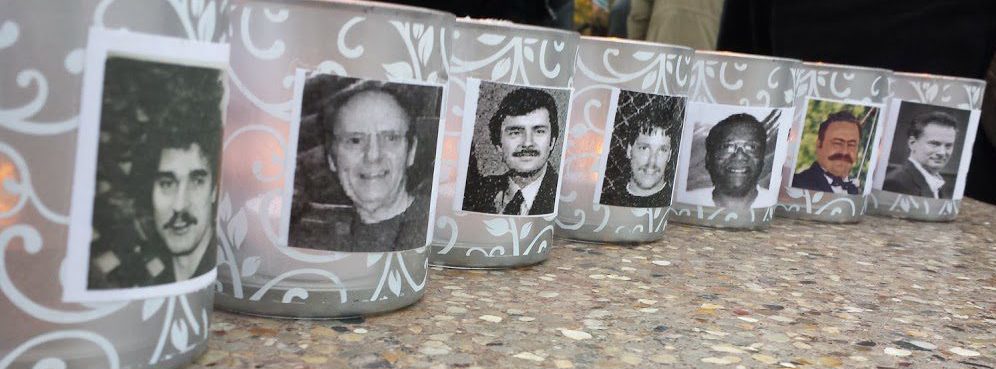

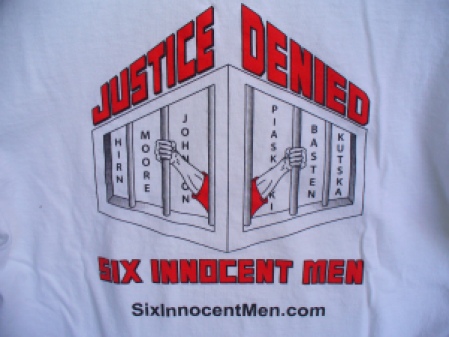

“We’ll have ninety minutes,” Máel said, and suggested October 27th as a possible date for my visit. “Perfect!” I said. “That’s the day before October 28th; the historical date in 1995 when the six men were convicted!” (Due to the arrival of the COVID-19 Pandemic, this class was done virtually.)

Keith Kutska at the 2015 evidentiary hearing in Green Bay, Wisconsin

In preparation for the class, I wrote to Keith and asked if he’d be willing to divulge the personal traumas his family had endured back then. “I believe your words will have the greatest impact on the students,” I reasoned. Keith thoughtfully and eagerly assembled these thoughts:

Greetings Ladies and Gentlemen. Thank you for your interest in this miscarriage of justice. In a sincere effort to inspire and instill in you, insight into how our criminal justice system sometime works, I’ve written down just a fraction of my firsthand experiences and personal observations. I also want to acknowledge the significant impact you will have on the future of that system as attorneys, prosecutors, judges, etc.

As this situation unfolded I was living in a small peaceful rural community in which my family still resides. All at once I was on the evening news being portrayed as the primary suspect in a high-profile homicide. I was overtly as well as covertly under surveillance for the next two years.

During this entire time I boldly stood behind my innocence while facing the questioning eyes of the people in our community. Those who knew me always offered their support along with their fear that the authorities were trying to frame me because I had hurt their pride (for obtaining and sharing the audio recording handed to me by an officer from the Green Bay Police Department).

I had lost my job and struggled to find employment. The monthly bills still had to be paid. On top of that I and my wife would also have to deal with mounting legal expenses. Needless to say, our financial assets quickly dwindled.

Family, friends, and neighbors watched with empathy as my wife and I struggled to retain and display confidence that the supportive facts of my innocence would prevail. Little did I know that the authorities would fabricate alternative facts and purposefully disregard the truth in order to obtain a conviction, thereby, repairing the tarnished image of the police department.

Until it’s been experienced firsthand, the psychological and stigmatizing trauma that I and my family have had to endure as a result of this travesty of injustice is beyond comprehension.

In addition, Keith offered these words of procured wisdom:

As future defenders of the law, it is imperative that you maintain a moral focus on the demanding principles required in the service to justice. Those principles, while sadly not always practiced, are well established within our criminal justice system:

- That accused citizens are actually presumed innocent and entitled to a defense that enforces the protection of the constitutional rights from prosecutorial overreach.

- That the state, while prosecuting its case with vigor, and not zealotry, be held to a high standard of proof to uncover and disclose every existing element of a crime beyond a reasonable doubt.

- Most importantly, that all hearings and trials be held in front of tribunals which are fair, objective, and impartial.

It is only under these governing principles that there can be any confidence of an outcome in which justice has been properly administered. Indeed, any failings in these principles will only ensure that innocent citizens will be victimized from a miscarriage of justice, guilty parties will maintain unwarranted liberties, the initial victims of crimes will be denied closure, and Lady Justice will be cheated out of her due rewards.

Below is a sampling of the outstanding, well-thought out questions Máel received from the students, some of which were addressed during my brief overview of more recent developments in the case. Unfortunately time ran out before we could get through all of them:

In the book, you touch on your personal struggles you have gone through in your life, as painful and hard to experience as they were, do you feel your experiences are part of why you felt so compelled to help these men?

What made you later publish a book about it?

What is your biggest struggle in advocating for people?

How did you begin your career as a social justice advocate? Was it this case that made you certain that this is what you should be doing in life?

From the book, I understood that this specific case impacted you unlike a lot of other cases. I wonder if there’s any other case that has moved or impacted you in the same way this has.

After this book was published and gained such recognition and awards, does that inspire you to write more books or get into wrongful convictions even more?

How did the public’s response to your book impact you? Did it help you open your eyes to new concepts or did it give you a new sense of empowerment since your words impacted so many other people?

Has anyone written to you saying you’ve encouraged them or gave them the motivation to also fight against wrongful convictions?

How do you feel the publication of your book has affected the way this case is looked at both publicly and in Green Bay? Has this collaboration of information and personal experience done anything to create change in both the case and the greater subject of wrongful convictions as a whole?

What is being done currently to help fully exonerate the six men? What is the state of their legal proceedings?

How can university students become involved in wrongful conviction cases or even become involved in the Monfils case?

I thoroughly enjoy listening to the innovative thinking of students, so after contributing more than ample time to the discussion, I wanted to give the students, 34 of them who were in attendance, a chance to voice their thoughts on what had motivated them to take this specific class, and to ask if they were aware of wrongful convictions prior to signing up for the class.

J.J. spoke up and said they didn’t know about wrongful convictions and that they wanted to learn more. J.J. is Black, so I pointed out the irony of not having been personally affected because of the overwhelming disparity of Blacks who are wrongfully convicted. They acknowledged this as a factor they are now aware of.

When I asked other students to explain what compelled them to take this class, E.M. shared that they’d like to become a police officer and felt it was necessary to learn about this problem to become a better enforcer of the law. I applauded the decision, saying they’re destined to become a great officer who will be armed with a valuable understanding of how our criminal justice system sometimes works. I compared this to how open-minded my former partner, Johnny, had been when I first told him about the Monfils case. “The expression on his face did not suggest he thought of me as some crazy person, rather it felt more like a look of genuine concern,” I contended.

Keith is an avid letter writer, so at the end of his message to the students he invited them to write to him and supplied them with his prison address. I encouraged them and Máel to consider reaching out to him. I also mentioned Keith’s upcoming parole hearing which will be scheduled in the early part of 2021. In response to the question of how they could help in the Monfils case directly, I proposed that a letter on Keith’s behalf to the Parole Commission would be most beneficial.

“Let me explain, I said. One thing I learned about the value of these letters is this. When people send in letters of support, it may not be acknowledged as positive support for the prisoner. But during one parole hearing in particular for one of our men, the commissioner assigned to his hearing made it a point to mention that not one letter of support had been received. It’s a way for them to intimidate, to manipulate, and to demean.”

The session ended. And while Máel directed the students to applaud their guest, I, in turn, applauded them for their interest, their motivation, and their willingness to be exposed to a topic that is extremely depressing, but one that they themselves could very well have a hand in changing…or at the very least, decreasing the likelihood of its recurrence!

As students left the session one by one, a brief and thoughtful message from H.A. appeared in the chat box. It read, “Thank you, Joan!”

Afterward, I realized I hadn’t asked the students for feedback regarding Keith’s letter. I reached out to one student who had friended me on FB after reading my book. I asked if they’d like to offer some. I was deeply touched by these inspiring words, filled with compassion:

“When I first got the news that Keith had written something for the class, I was shocked that one of the six wrongfully convicted men wanted to talk with the class about his story. I was also excited to read the letter, so I can learn a little bit more about the case as well as learn more about who Keith is. After reading the powerful letter that Keith wrote, I felt more educated about the struggles he faced before and during his incarceration. Keith also has inspired me to push even harder to fix the many issues that are currently occurring in the criminal justice system. My dream job has always been to be a part of the Innocence Project and Keith’s letter and story is also showing me that my dream job can become a reality because there is a need for people to fight for others when others cannot fight for themselves. I am also happy that Keith included his mailing address so I can write to him and keep up on the case as it still develops. I am extremely honored to have been part of the wrongful convictions class at Hamline University as well as had the honor to have talked to a person who has experienced the many injustices of the criminal justice system first hand. Sincerely, L.C.”